Racing to Cross the Atlantic

Imagine a time when crossing the ocean by air wasn’t just a routine — it was an act of pure daring. The world of the 1930s was brimming with ambition, and the skies above the Atlantic remained the last great frontier. For Pan American Airways founder Juan Trippe, that vast stretch of water wasn’t an obstacle — it was a destiny waiting to be claimed.

But ambition alone wasn’t enough. International politics, stubborn rivalries, and national pride all tangled the Atlantic like a net. Foreign powers like Britain and Portugal guarded their landing rights fiercely, forcing Trippe to turn westward — toward the Pacific — until the tides of diplomacy shifted.

By the summer of 1937, the doors to the Atlantic finally began to creak open. Portugal agreed to host American planes at the Azores, and Britain, watching Pan Am’s sweeping success across the Pacific, agreed to share the skies — but not without conditions.

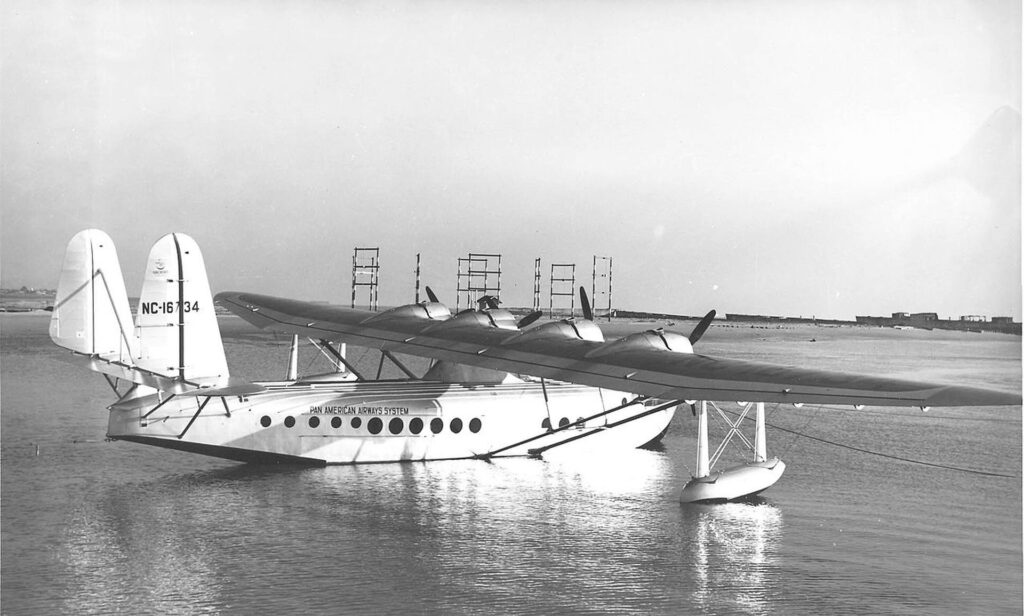

Britain would grant landing rights on its territory only if the U.S. returned the favor. And just like that, a joint Anglo-American partnership was born. On one side stood Britain’s Short S.23 Caledonia — a majestic four-engine flying boat built by Short Brothers, featuring a two-deck layout and advanced Gouge flaps that made heavy ocean takeoffs possible. Originally designed for colonial routes, the Caledonia had to be modified with special fuel tanks to handle the longer Atlantic crossing.

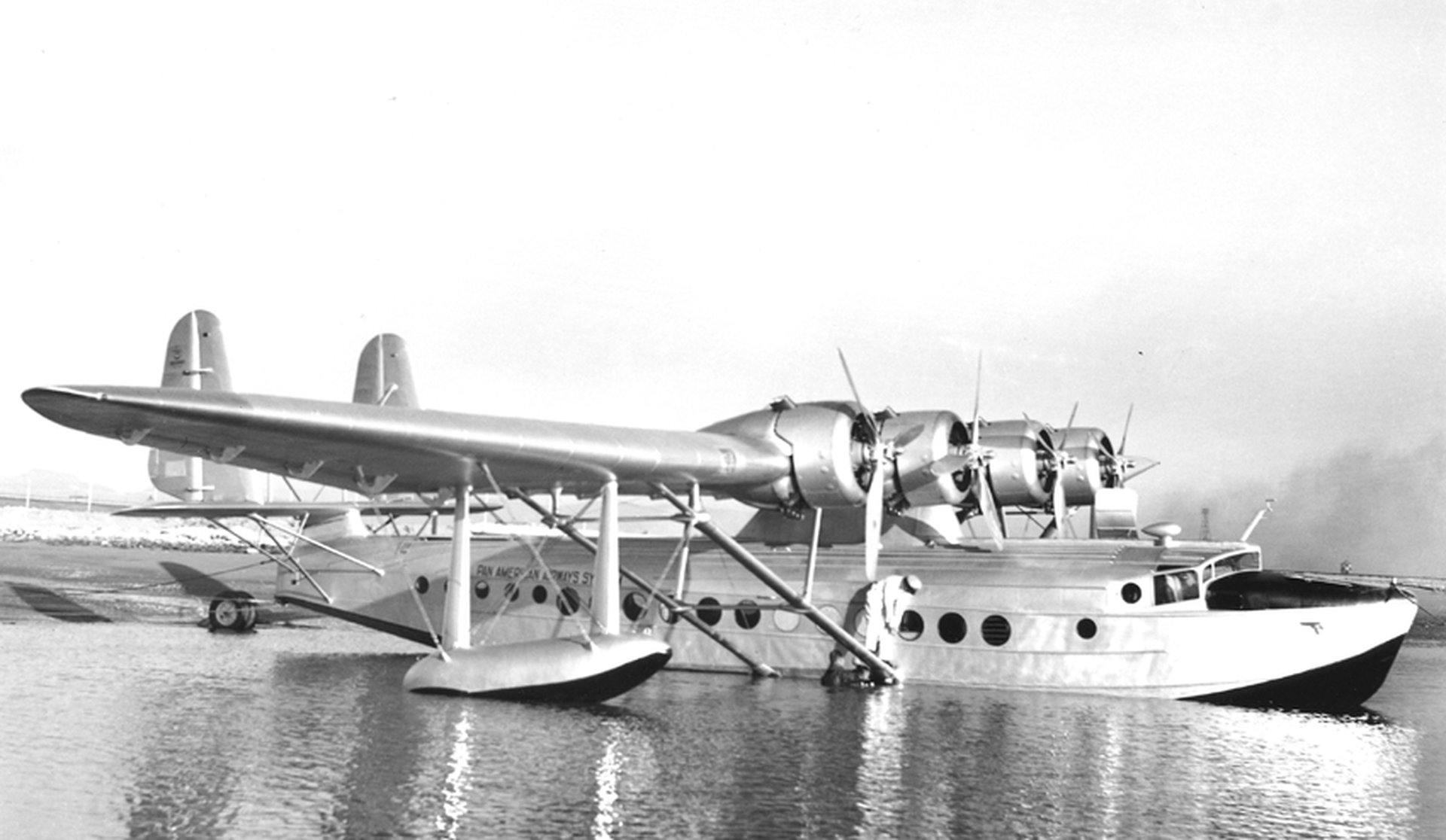

On the American side was the Sikorsky S-42B Clipper — a sleek, long-range marvel developed under Trippe’s direction for Pan Am’s global expansion. With a standard cruising range of 1,220 miles, the Clipper outperformed the British aircraft on endurance and speed and had already proven itself over the Pacific.

Though Britain was new to the game of long-distance overwater flight, Pan Am already had years of experience. Still, politics required the Americans to hold off until the British were ready. What could have been Pan Am’s solo triumph turned into a coordinated effort. By delaying service until the Short boats were completed, Pan Am had to wait years before finally opening its Atlantic route.

That joint venture would finally come to life in 1937 with survey flights between Hamilton, Bermuda, and Port Washington, New York — a symbolic gateway to Europe. It was the start of something much bigger: regular transatlantic air travel.

The article “Wings Across the Seas,” published in the October 1937 issue of Popular Aviation, captured the moment when the Atlantic was no longer an unreachable barrier, but a bridge in progress. It reflected not just a technological achievement, but the shifting tides of international cooperation.

“Wings Across The Seas,” published by the editor in the October 1937 issue of Popular Aviation magazine.

Long before the Pacific, Juan T. L Trippe wanted the Atlantic. But Trippe’s far-sighted plans for his Pan American Airways were successfully stymied by “competing” foreign nations (England, Portugal, et al.). So, instead of devoting his major energies toward overcoming the Atlantic pitfalls, Trippe turned his company westward.

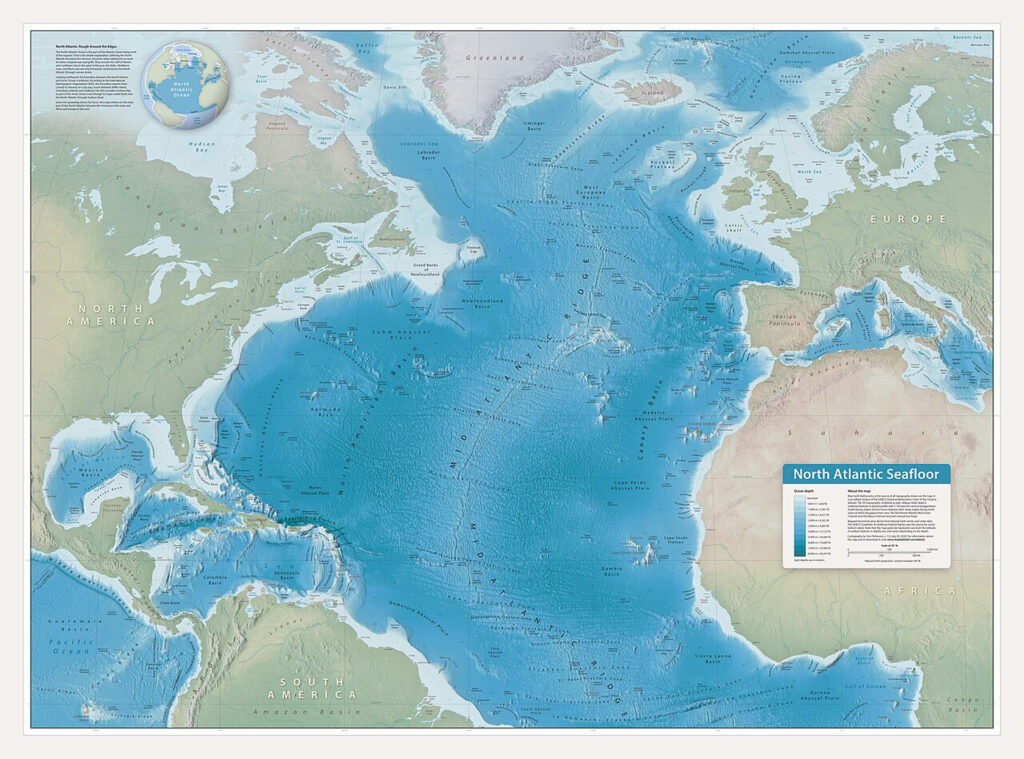

With Pan American’s success in Pacific operations assured, Trippe again turned to the Atlantic. By this time Portugal had agreed to give the Americans landing rights tentatively planned at the Azores and possibly Portugal itself. This was—and probably will be- the summer route of the trans-Atlantic airliners of England and America.

Britain, meanwhile, noting the success of the Americans in the Pacific and the willingness of the Yankees to cooperate on the Atlantic, gave in. Gave in, that is, to the extent that landing rights on British territory would be granted if, in turn, the Americans would grant the Englishmen the same privilege.

Boiled down, it meant just what we are seeing today and what the photographs on this and the opposite page signify: the Americans must “cut in” the English or not fly the route at all.

When the agreement “cutting in” the British finally was closed, that country’s air ministry immediately announced that orders for a large fleet of four-engined flying boats had been given to Short Brothers, famed old-time British airplane builder. The Caledonia, shown in the accompanying photographs, is one of the Short Empire boats, as they are technically known.

But, though the British were entering a virgin field by comparison to Pan American, the Americans already had had years of experience at long-distance over-water flying. Nonetheless, the Americans were forced to hold up their long planned flights to Bermuda and England until the Short boats could be completed. If it hadn’t been for these delays, the Americans could have been flying the Atlantic three years ago.

The service recently opened between Bermuda (British territory) and the United States also could have been in operation at least three years ago. But again Pan American was forced to wait for the government-subsidized Imperial Airways to get its Short boats. Consequently, the joint British-American service between Hamilton, Bermuda, and Port Washington, N. Y., was officially opened just last month.

The Short and Sikorsky “competitors” on the Atlantic line compare almost equally. But the American ship has the edge on the Short boat in its standard cruising range. Where the Sikorsky has a range of 1,220 miles, the Short boat has a standard range of 730 miles. However, special fuel tanks were installed in Caledonia for the Atlantic flights.

Today, the Short Caledonia and Sikorsky Clipper may seem like relics from another age, but they were the titans that helped turn an impossible dream into a practical reality.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this story, be sure to subscribe to the blog, leave a comment below, and share with fellow aviation enthusiasts!

Discover more from Buffalo Air-Park

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.