Adventures in the Frozen Wilds of Canada

Alright, let’s dive into today’s story!

Imagine a vast, untamed wilderness—an expanse of snow and ice stretching as far as the eye can see. The wind howls through the endless pines, whispering tales of explorers and frontiersmen who dared to brave the unknown. Somewhere in this frozen expanse, a lone aircraft cuts through the sky, its engine roaring against the silence of the wild. Inside, bundled against the biting cold, sits a man whose very existence is a testament to resilience—Captain D. S. Bondurant.

This isn’t your typical aviation story. Bondurant wasn’t just another pilot flying predictable routes; he was an adventurer in every sense of the word, charting territories where maps failed and survival often hinged on sheer grit. From emergency landings in subzero temperatures to encounters with indigenous communities who had never before seen an airplane, his journey is one of courage, resourcefulness, and a deep love for the untamed north.

So, join me as we step into the cockpit of history, retracing the incredible exploits of a man who turned the frozen wilds of Canada into his own personal airfield. This is Adventures in the Frozen Wilds of Canada—a tale of aviation, endurance, and the relentless human spirit.

“Adventures in the Frozen Wilds of Canada” by James Montagnes, published in the September 1931 issue of Popular Aviation.

Captain D. S. Bondurant is an aviator who is as much at home piloting a plane over unknown territory in the Canadian hinterland as he is flying along a regular air mail route. He can make friends with Indians and Eskimos as readily as he can with fellow pilots at any airport.

Born in Cairo, Illinois, this auburn haired pilot with a pumpkin-red mustache, is reputed to have been for some half dozen or more years the only American citizen allowed to fly Canadian transport planes. Coming to the Dominion after a barnstorming career following his service with the American Air Force in France, he has been flying in the northland ever since.

Bondurant’s first contact with the unknown northland came during the gold rush days of 1925-26, when every plane of every description was bundled to the hopping off points on the transcontinental railway across Northern Ontario and Quebec. Here the jovial pilot with his southern drawl flew prospectors and freight in and out of the bush in an old war time ship.

Winter and summer he flew, heading farther north of the railway each day as more and more men came in to stake their fortune in the unexplored bushland. It was hard flying in all sorts of weather, with the possibilities of weeks of privation and hardship in case of a crash or forced landing in that isolated country.

On one flight he had a crash. He had set out in forty-five below zero weather, with his ski-equipped plane. Something went wrong when twelve miles from the outpost. The machine came down and sank its nose in a ten foot bank of snow. Bondurant was stranded. Help would not come. There was nothing to do but get back to the outpost.

So he set out in forty-five below zero, wearing only his heavy flying kit, no skiis, no snowshoes. He tramped through the bush, often sinking deep in snowdrifts. But he made the post that day. He came in black, his face frozen, his hands frozen, and his feet hardly able to carry him.

They thawed him out till his little mustache became sprightly again. Then Bondurant set out with a gang, a small stove, a tent, and many tools, to dig out his ship and to thaw out her engine. Just two days after leaving the post on his flight he arrived at his destination, though he felt the results of his walk for weeks.

Bondurant has since that time flown the entire northland of eastern Canada. He has been places where no other aviator has ventured before or since. On many a trip carrying geologists, food supplies and mining equipment, he has had to make his own maps. The best Government maps were not detailed enough. And on those flights Bondurant has drawn maps showing the landmarks in regions where ninety per cent of the country was water, though government maps had shown vast stretches of land. His resourcefulness and skill as a pilot and a woodsman have helped him out of many a tight corner.

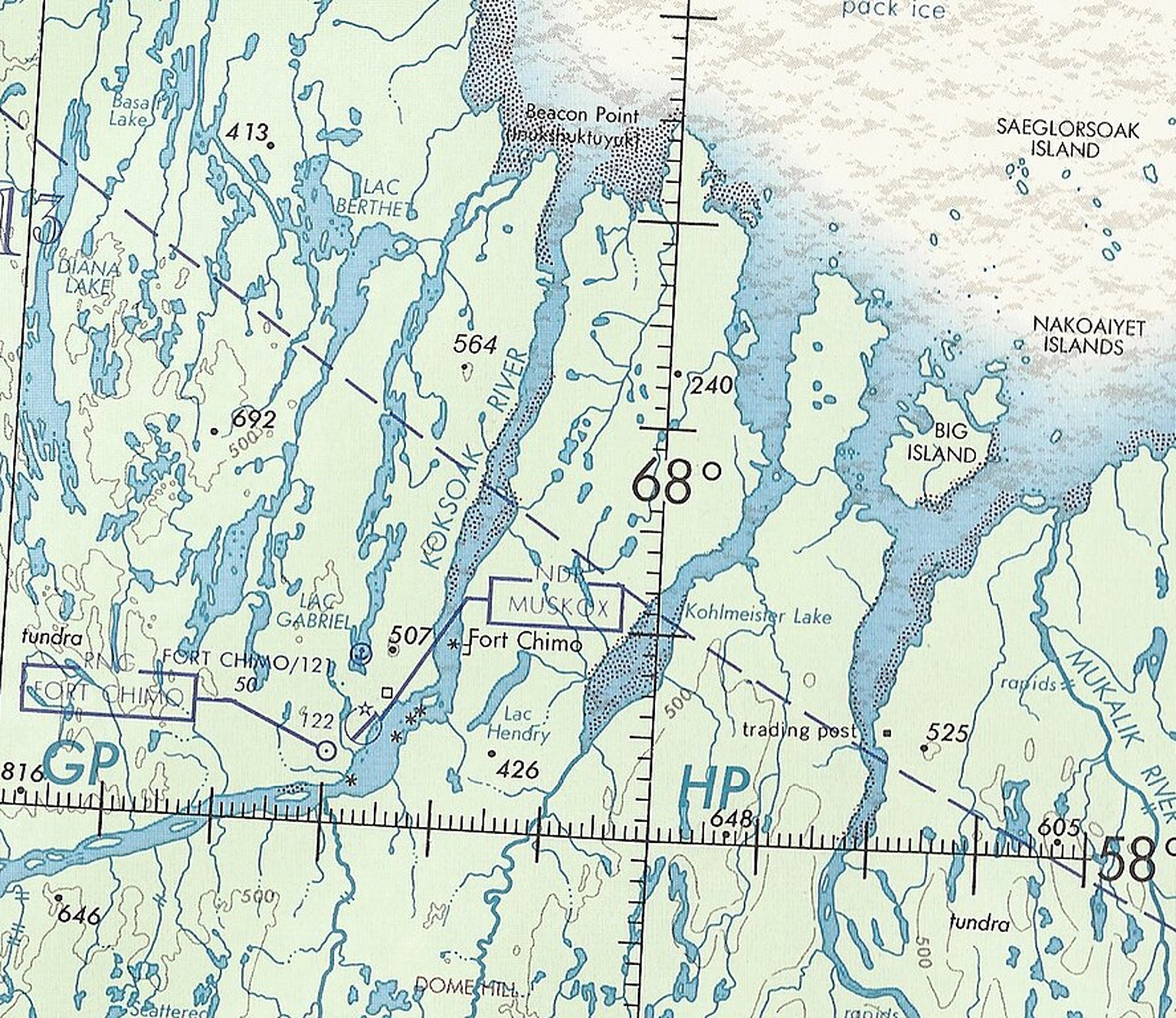

It was on a flight from Seven Islands, on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, to Fort Chimo, seven hundred miles to the north on Ungava Bay, that he came as near being stranded as he ever wants to be. He had with him a geologist and a mechanic, with enough food for one day, as they hoped to make their destination with only one overnight stop. Before they had gone many hours a storm came up. It seemed the best policy to come down to park on one of the innumerable lakes.

Hour after hour they sat in their plane. Night came but the storm continued. The plane rode the waves on its pontoons. Came morning and no sign of a let-up. It was useless to go ashore, for timber did not exist there.

They would find no better shelter than where they were. They managed a cold breakfast and waited. They passed the day and night.

In all they sat in their plane for 50 hours, unable to move much because all available space had been used to carry prospecting equipment. The food was all gone after two days. For awhile it looked as if another plane might be lost in the cause of the mineral exploration of Canada. But with the first sign of a let-up in the storm, Bondurant made the plane rise from that lake and did not set her down again till Fort Chimo appeared below.

Like an explorer of old, he has come down to Indian settlements where no plane has ever been before. As in the days of long ago, when the Indians feared the big ships the palefaces came in, so they at first were scared of the “big bee” in which the white man came out of the sky. Bondurant tells the story of his arrival at one post in the hinterland of Northern Quebec.

As he was coming down he was surprised to see about a hundred Indians loping for the bush as fast as they could go, while one lone man advanced to the shore. Down came the plane, and just at the bush line the Indians stopped. Bondurant and his party stepped out, waded ashore, were welcomed by the only white man at this fur post, and then were surrounded by Indians of all sizes and ages.

They wanted to shake hands, and Bondurant was kept busy shaking hands all day, each Indian coming back several times to shake hands again. They had never seen a plane before. When “Bon” started to take pictures with his small camera, there was no holding the natives. Nothing less than that he should take picture after picture, though after using up three rolls of film, the camera was empty, while the shutter continued to snap at braves and papooses while daylight lasted.

When Indians told him at Seven Islands that there was inland a water fall from which the roar could be heard fifty miles distant when travelling by canoe, Bondurant was somewhat skeptical. But the cataract was on his way to Fort Chimo, and he decided to investigate on one trip. He heard the falls twenty miles away above the roar of his 400 horse power engine. At ten miles distance the air became bumpy. A heavy mist screen arose. Down went the plane, into the mist. Up she bounded a hundred feet. The air was decidedly bumpy. The water fall below over a cliff 302 feet high, and above and below rapids spread for many miles.

With his small camera Bondurant began to take pictures of the falls and the rapids, his plane as low as was safe, riding the air like a ship in a storm. Later Bondurant learned this bit of dangerous flying had not been in vain. His were the first aerial pictures to have been taken of Grand Falls on the Hamilton River in Labrador, estimated to have more hydro-electric energy than Niagara.

In preference to flying the air mail routes between cities, which Bondurant does from time to time, he likes the unknown northland. “It is more dangerous,” he will tell you, “but I like it better.”

Great story, right? Anyway, see you in the next one!

Discover more from Buffalo Air-Park

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.