Air Travel? Not So Fast.

In the October 1928 issue of Popular Aviation magazine, the editor penned a thoughtful and surprisingly skeptical editorial titled “An Outsider Looks at Aviation.” Though he claimed to be no expert, his observations read like those of someone who understood that aviation wasn’t just a marvel of engineering—it was about to challenge the entire structure of modern transportation.

And yet, he wasn’t sure it could pull it off.

Reading it today, nearly a century later, is like peering into a moment of honest uncertainty. The editorial feels less like a critique and more like someone trying to wrap their head around a fast-moving, barely-controlled revolution—something many of us can relate to when it comes to electric vehicles, AI, or space travel today.

A Skeptical but Curious Mind

The author opened by acknowledging that airplanes were fast—unquestionably the fastest method for moving people and goods over long distances. But he quickly questioned whether that speed translated into meaningful value for the average traveler or shipping company.

“It is possible to have so poorly located a terminal that all the advantage of speedy transportation is lost.”

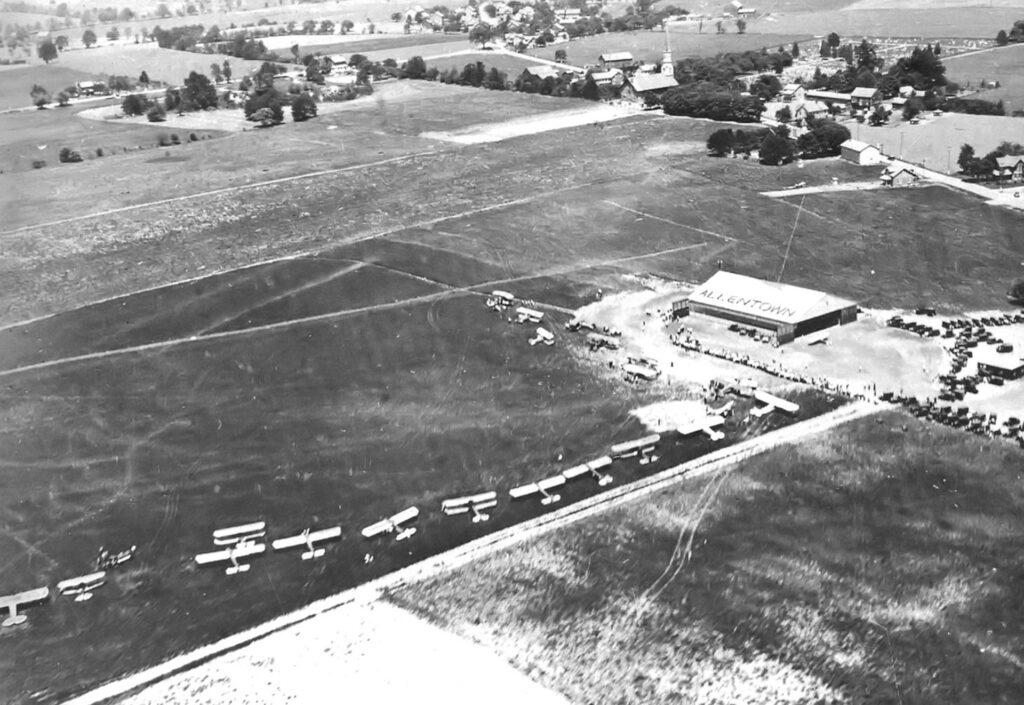

That single sentence captures one of aviation’s earliest—and longest-running—challenges: the airport.

In 1928, most airfields were located well outside major city centers. Often, travelers had to spend 30 minutes to an hour just getting to the airport. That meant a 100-mile flight might take less time in the air, but the total trip could be slower than taking the train from downtown to downtown.

He wondered aloud whether airports could ever be integrated more closely with cities, or even with other forms of transportation like rail or bus lines. He saw promise in partnerships like Transcontinental Air Transport, an early attempt to link air and rail travel for coast-to-coast service. But the infrastructure simply wasn’t there yet.

Planes vs. Trains

Just like the railroads of the 19th century, aviation would need to develop a complex support system: terminals, baggage handling, logistics, maintenance, passenger comfort, and staff to make it all work behind the scenes.

And that was the heart of the editor’s concern—aviation wasn’t just about the airplanes. It was about building an entire ecosystem. Railroads had already fought and won that battle, developing specialized infrastructure and huge support teams. Now, aviation was trying to leap ahead—without that same foundation.

He asked if the industry was taking lessons from the past, or if it was too eager to race ahead without the support structures needed to last.

That support started with terminals. Unlike the railroads, which often had the luxury of building right through downtowns and scooping up cheap land early, airports were already playing catch-up. Cities had grown without them, and now aviation had to fit into spaces that weren’t designed for it—often pushed to the outskirts where land was cheaper and larger plots were available.

He even wondered aloud if airports might one day be built right on top of rail lines, combining the speed of aviation with the accessibility of the train. That kind of intermodal vision may have sounded ambitious in 1928, but it was surprisingly forward-thinking.

Comfort and Convenience Matter

Beyond the logistics, the editor touched on something that still rings true: people won’t choose speed over comfort indefinitely.

“One of the things is speed, but the other is comfort.”

Airplanes might get you there faster, but that didn’t matter much if you were bouncing around in a cold metal tube with no food and no real terminal to wait in. Compared to the elegant lounges and sleeping cars of the railroads, early air travel felt more like an expedition than a journey.

He wasn’t blaming the aviation companies—he knew they were still focused on hauling mail—but he predicted that once passenger traffic picked up, travelers would demand more than a quick flight. They’d want meals, clean terminals, helpful staff, and warm coffee—especially if they were paying a premium.

That’s exactly what happened in the decades to come. But in 1928? Air travel still had a reputation for being a bit rugged and experimental.

Aviation’s Mail-First Mindset

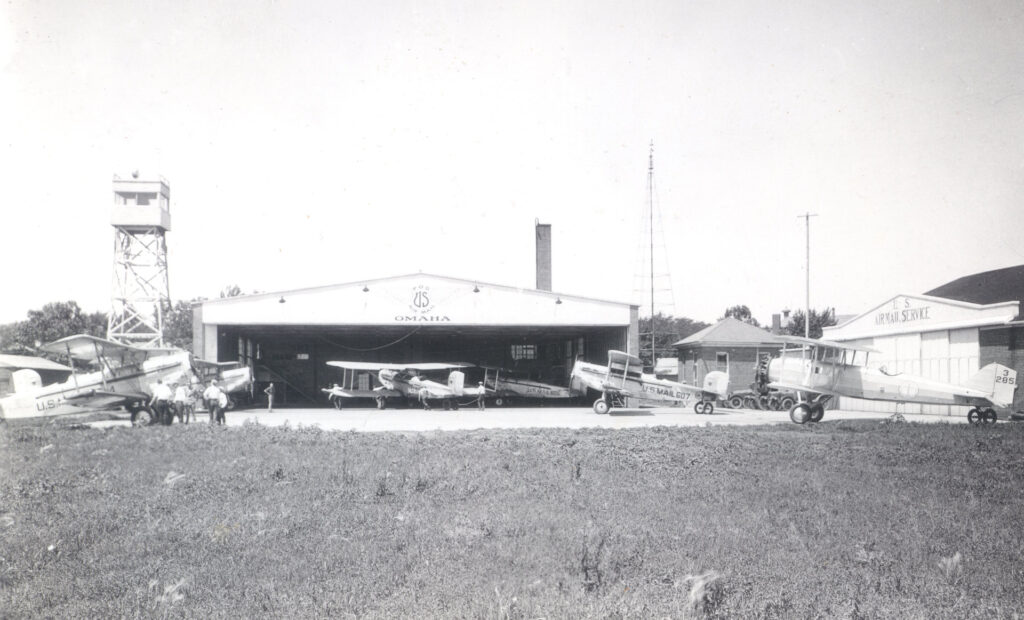

One of the editorial’s most accurate predictions was about air mail. The editor believed that while commercial aviation still had hurdles to clear, mail didn’t care about comfort. It needed speed—and air travel offered it.

He imagined a future where nearly all letter mail in the U.S. would move by plane. And for decades, that’s exactly what happened.

In fact, many of today’s major airlines—United, American, Eastern—got their start as air mail carriers. The U.S. government subsidized routes, helping these companies grow and eventually expand into passenger service.

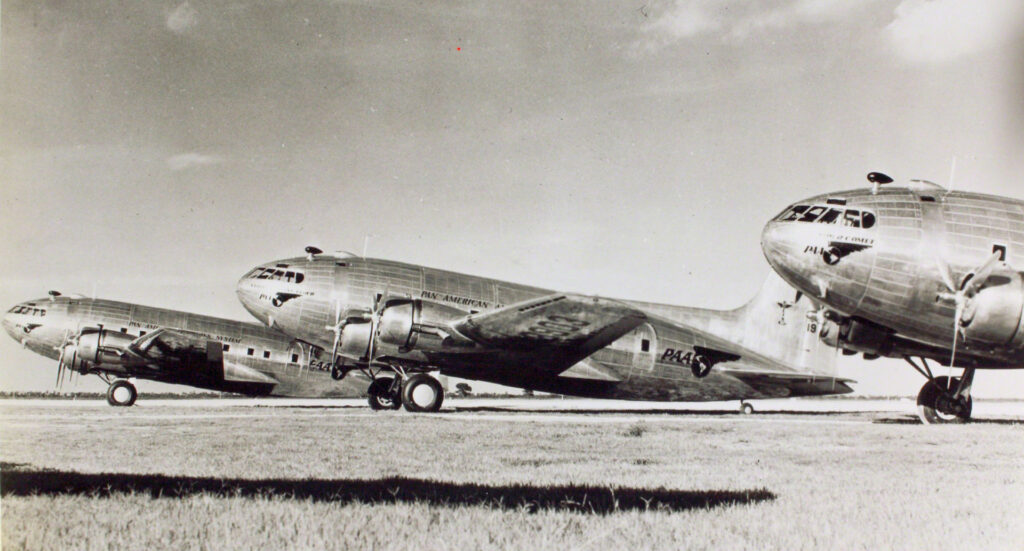

The editor even predicted that passenger planes and freight planes would evolve into separate designs, much like how railroads separated their Pullman sleepers from their boxcars. That, too, came true—with the rise of dedicated cargo aircraft like the DC-3 freighter, the Boeing 747F, and modern FedEx and UPS fleets.

It Takes More Than Just Pilots

One of the most forward-thinking parts of the editorial was its focus on aviation’s workforce. In 1928, most of the attention was on pilots. They were the public face of the industry—the daring flyers, the test pilots, the war heroes.

But the editor warned that aviation couldn’t thrive on pilots alone.

“There ought to be at least ten good places on the ground for every one in the air.”

He understood that successful transportation systems rely on a whole team of professionals behind the scenes: ticket agents, mechanics, dispatchers, freight handlers, schedulers, marketers, accountants. He asked whether anyone was thinking about training those people—because without them, planes weren’t going anywhere.

He even suggested that the aviation industry might be wise to hire experienced railroad staff, many of whom already understood logistics and transportation systems. And that’s exactly what some early airlines did—pulling talent from shipping, rail, and postal services to get their operations off the ground.

From Doubt to Dominance

What makes this editorial so compelling isn’t that the editor got everything right—it’s that he was asking all the right questions. He wasn’t dismissive. He was practical. Thoughtful. Curious. And most importantly, he understood that progress wasn’t just about invention—it was about infrastructure.

Looking back from today’s perspective, when air travel is not just common but essential, it’s fascinating to realize how uncertain its future once was. Airports were too far. Comfort was lacking. Infrastructure didn’t exist yet. And the public wasn’t convinced.

But aviation did overcome those early hurdles. It adapted. It evolved. And it became the foundation for a global transportation network that we now take for granted.

The editor ended his piece with a question: was the industry preparing itself for what it would take to succeed? As history shows us—the answer was yes. Eventually.

Until next time, keep your eyes on the skies!

Discover more from Buffalo Air-Park

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.