Tony’s Short Stories: A Forced Landing

In the early days of aviation, flying was as much an adventure as it was a test of skill, courage, and resilience. Lady Heath, a pioneering aviator and one of the first women to hold a commercial pilot’s license, stood out as a shining example of these qualities.

In this article, originally published in Popular Aviation and Aeronautics in February 1929, she recounts a particularly challenging leg of an international light aeroplane competition in France. Her narrative offers a vivid glimpse into the trials and tribulations faced by early aviators, where every flight was a battle against the elements, mechanical failures, and the unknown.

This story highlights the technical and physical demands of flying in that era. It captures the indomitable spirit of those who pushed the boundaries of what was possible in the sky.

A Forced Landing

By Lady Heath

Published in Popular Aviation and Aeronautics, February 1929

Twenty six aeroplanes entered for the International light aeroplane competitions in France last September. Twenty six little machines of all types and shapes and nationalities.

Some crashed, some got tired, some got lost, and only four finished up the 2,000 mile reliability tour of France. My little Avro Avian equipped with a Mark Three Cirrus engine, now being made in this country, was one of the fortunate four, but it was only by repeated luck and extraordinary hard work that we persuaded it to get round.

After we had finished with take off, landings, climb, speed, petrol consumption, and all other troubles that make an international competition we were forced to wander around France to show that our poor little overworked hacks could tour as well as perform.

The next to the last lap of the tour was from Nantes to Le Havre, a distance of about 200 miles. We had to carry our full load on the machines in the shape of sand bags, and the pilots on the tour consequently felt rather hot-and-bothered at the thought of piling in their kit as well. A beautiful solution presented itself, and I sent to England for my privately owned Moth to accompany the tour carrying the spares and suit cases of all the competitors with an amateur pilot, a friend of mine, at the joy stick. We called it the “Coeval de baggage.”

I had a little carburetor trouble at Bordeaux, and so decided to exchange my carburetor with that on our baggage hack. This was speedily effected at Nantes. There was no time for petrol tests or re-arrangement of jets as a prize was given at Le Havre for the first machine in, so one had to start at the crack of dawn, after working half the night. My mechanic was a wonderful worker.

I put my sand bags in front and on top of them I had one of the keenest and most enthusiastic passengers I have ever had the pleasure of traveling with, Mr. John Webb, one of the foremen of the company which makes the English Cirrus, who had come as my mechanic as every French town was giving the pilots so many public receptions that we had no time to work on our own aeroplanes.

“Webbie” in not a pilot himself, but he knows more about engines than most people I know. I always look on it as a great compliment that he trusts me in races and competition, and all sorts of difficult situations, to keep his skin whole.

We were flying into a strong wind and were making slow time as we passed over the beautiful towns and forests of Mayenne with blue lakes shining between them. Our petrol consumption seemed to me horribly high. We had evidently left the feed far too rich. My indicator needle was dropping with alarming rapidity. I did not worry much, as the farther north I went, the more beautiful were the forced landing fields that spread out before us. When we got as far on our route as Bourguebus, I realized that I would just have too little gasoline left to take me into Le Havre, and so I turned to Caen where there is a combination of town, river road, and railway and where we hoped to get the best fuel possible.

We just got to the edge of Caen when the petrol supply failed us and we scrambled down into a field by the road leading northwards into the town. Naturally, the excitement was intense, and in five minutes the machine was surrounded by hundreds of small children of all shapes and sizes.

Webb and I shook hands. We always shake hands when anything of interest happens. I don’t know why-it brings us back to the normal probably. Then, we proceeded to cajole the most intelligent French child to go to the nearest garage and buy us a lot of “Essence.” The “Essence” duly arrived in gallon tins and we filled up, realizing it was very bad motor fuel but it was all we could get. Having done this and cut down our petrol consumption a bit, we persuaded some of the local police to keep the children at bay and we took off out of our little field. On we went to our destination with a beautiful guide beneath us, the River Orne and the Deauville coast line. We flew low along the level sands waving as we passed to crowds of bathers and little fishing boats near the shore.

At Trouville, we turned directly North and went out across the estuary of the Seine. The other side was somewhat obscured by mist although it was but 10 short miles. I thought it advisable, having precious Webb on board, to climb high for safety. Thank goodness we did.

When we were five miles out to sea with Trouville’s numerous sand castles and bathers behind us, with its hundreds of bathers disporting themselves in the surf, and the piers of Le Havre before us beginning to take definite shape, suddenly there was a crash, a bang, and a clatter and instinctively the nose went down and we turned back towards the land. We had luck. The engine died, but occasionally it caught a few revolutions that pulled one nearer to that safe white line of surf on the shore.

The bathers, the sand castles and the striped umbrellas made Trouville beach gaudy and terrifying. In the line of the surf we had water that was too shallow for the bathers and too wet for sand castles and the Avian sat down in it, the starboard wing missing a little old lady complete with her knitting, by a hairsbreadth.

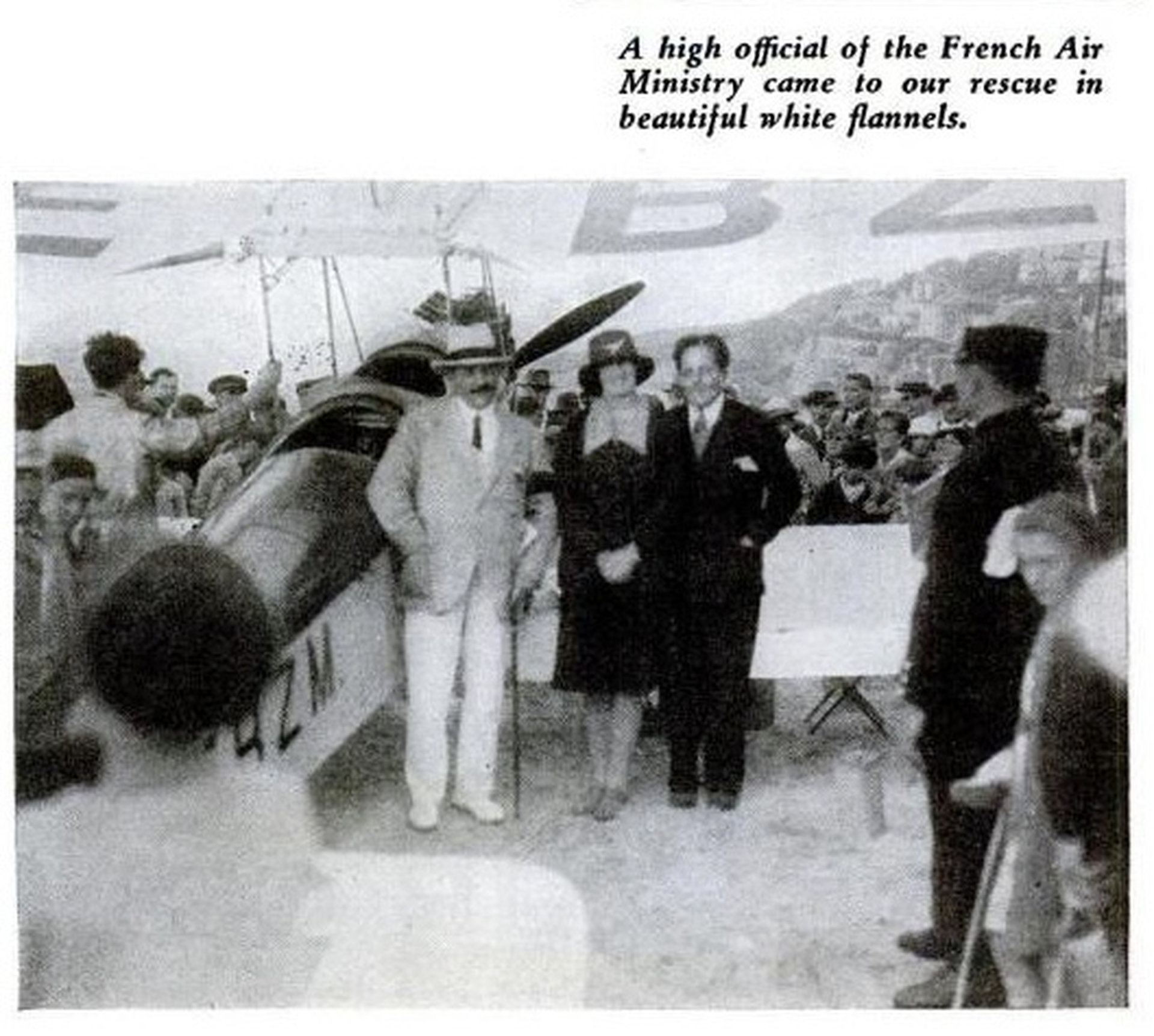

We shook hands again! By a marvelous stroke of luck there appeared on the scene a high official of the French Air Ministry, complete with summer flannels, full of good advice, and he dashed me to a telephone to get in touch with Le Havre while the faithful Webb proceeded to trace the trouble. We found that the terrible motor fuel we had put in had seriously damaged a piston face, and a ring had broken and chewed up everything in the neighborhood.

Soon the baggage Moth appeared in the skies replete with the spares I had telephoned for, but what was our horror and chagrin to see it miss us and sail right over our heads and proceed to look for us miles further down the beach. I wish you could have seen Deauville Beach at that moment. The French high official recruited all his friends and they had gathered an army of small children to flatten out every miniature castle and hollow in one section of the beach, and we marked it out as an improvised aerodrome with towels and newspapers.

Further back was my Avian, under whose wing French hospitality had spread us a luncheon of vin blanc, long French rolls and some sliced ham.

We worked like ants taking everything to pieces. Suddenly the baggage Moth caught sight of us, and glided down to a perfect landing near us on the cleared sand. Webb waved me aside as soon as he got his new pistons and cylinders. It was impossible for two people to stand up on the rickety chair which was our trestle and so I employed myself taking our hosts up for joy rides in the “baggage Moth.” Even the French high official let his family go up when he saw that it had come down once safely. It made me very happy to find that a rival competitor had taken the Moth, as its “driver” could not be found, and, with true sporting spirit, flown the spares and some good gasoline over to me.

We worked until the faint stars come out, and a crescent moon rose in the dark blue sky and then we hauled the machines above high water line and fastened them down for the night.

The sun had just come back to the countryside of France next morning when we tackled the cylinders again, and at six o’clock, the last nut and bolt was screwed down and the Cirrus was ticking over with her old monotonous regularity. The tide was out that morning and its path made a wonderful natural flying field.

Very gingerly we ran her up chocked up with gasoline cans and although she was down in revs a little, she was fairly steady. We climbed and circled about the beach for a quarter hour before we ventured across the estuary. The faithful baggage Moth did the tour as reliably as any of the competition machines hovering kindly in the near foreground.

We touched ground at Le Havre at five minutes past eight. The aeroplanes were all ready to leave on the day’s lap at eight o’clock and had to check in at the end of the day’s journey by four, so that we had a simple matter before us to do the 200 kilometers into Paris where the competition ended.

Never shall I forget that journey. Racing along the valley of the Seine, over water and forest trying to make good time, and every moment when a single revolution was lost, going through the pangs of another forced landing!

Well, she got to Paris and there we gave the unfortunate little engine a top overhauling, a better one than we had given her overnight on the beach. Without any exaggeration, we took a teaspoonful of sand out of the petrol filter and another teaspoonful of aluminum filings out of the oil pump.

To our great surprise, the final French reaction was one of entire unconcern. One would think that strange damaged aeroplanes floated in out of the sky, to their beaches and among their bathers every day of the week.

The most distinct recollection I have, gliding in towards land over that water, with the engine spitting and misfiring and finally stopping, and with a hundred holiday makers before me and the wet wet water underneath, is the sight of Webb’s face in the cockpit. He had pulled his cap off, and he had his arms up on the decking to protect his face if we hit anything hard. But he had an utterly unmoved expression, a complete poker face, but, a pure white complexion with a green tinge, and a crop of hair that in spite of the rushing air, was standing up straight and stiff and terrified.

Praises be that his premonitions were for naught.

“A Forced Landing” is more than just an account of an aviation mishap; it is a testament to the determination and ingenuity required to navigate the unpredictable world of early flight.

Lady Heath’s experience underscores the importance of quick thinking, teamwork, and the occasional bit of luck in overcoming obstacles. While her story is filled with tension and uncertainty, it also reveals the camaraderie and support that existed among aviators and their crews.

As we look back on these early feats of aviation, we are reminded of the tremendous progress that has been made and of the courage and resolve of those who laid the groundwork for today’s aeronautical achievements.

Lady Heath’s legacy, along with that of her contemporaries, continues to inspire new generations of pilots and aviation enthusiasts alike.

Interesting, right? I hope you enjoyed this short story as much as I did. Thanks again for making it to the end, and I’ll see you in the next one!

Discover more from Buffalo Air-Park

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.