Tony’s Short Stories: A Forced Landing in the Bahamas

As a kid, I spent many hours flying in my father’s Cessna 310, but the most memorable trip was to the Bahamas in the early 1970s. We developed an oil pressure issue and had to land at the North Bimini Airport. After determining that a loose oil drain plug was the issue, my father decided it was best to return to the airport in Pompano Beach, Florida, for repairs.

But as we were getting ready to take off, the latch to the passenger door broke. Luckily, we traveled with a close family friend and later my brother-in-law, Greg Zagon. He devised an ingenious idea by using a piece of a wooden broom handle to hold the door closed, which he held onto the entire flight back to Pompano. It wasn’t the most enjoyable flight, with the air rushing past the unsealed door, but we made it back safely, less maybe our ringing ears and Greg’s sore hands.

When I stumbled upon this article about a similar issue flying in the Bahamas, I felt an instant connection and knew I had to share it with you. It’s like our own little aviation adventure, isn’t it?

“A Forced Landing in the Bahamas” recounts a dramatic and gripping real-life adventure experienced by Gordon Bazely, an artist and adventurer, and Captain Arthur Holland, a seasoned Royal Air Force pilot. Set against the stunning yet perilous backdrop of the Bahamian islands, the story captures the landscape’s raw beauty and the sea’s unforgiving nature. In a time when aviation was still developing, Bazely’s account reflects the danger, excitement, and resourcefulness required of early air travel. Initially published in Popular Aviation in January 1929, this narrative provides readers with a thrilling, firsthand look at the challenges faced during a stormy flight and the remarkable survival that followed.

“A Forced Landing in the Bahamas”

By Gordon Bazely

Published in Popular Aviation, January, 1929

Gordon Bazely, of the British Water Color Society, is an artist and etcher. He was born in Penzance, England, 27 years ago. He received his education at Goldsmith’s College, London, and has been in the Bahamas for two years.

Arthur R.C. Holland was a captain in the Royal Air Force. He is English, is about 30 years of age, and has been flying for the last ten years, with the record of never having lost a passenger. Captain Holland is pilot and part-owner of the “Topsy Fish”.

Two schooners which had been lying at Gun Cay in the Bahama Islands were feared lost in the storm which swept over that locality some three weeks ago, and when I received a telephone call from Captain Arthur Holland of the seaplane Topsy Fish asking me if I would care to accompany him on a trip to Bimini and Gun Cay in search of the two vessels, it is not surprising that I ignored lunch in a hurried dash to the slipway from which the Topsy Fish was wont to slide into the beautiful waters of Nassau harbor.

Armed with a camera and binoculars and dressed only in our linen suits, we set out at about 1:30 p.m., August 8th, and making east towards the Fort Montagu Hotel we circled gracefully over Hog Island and proceeded down-wind towards Andros Island, some 40 miles west.

There is no better way of seeing the Bahamas than from the air. The wonderfully transparent sea, in its shimmering, ever-varying tones of emerald and turquoise, takes on more wonderful hues from the sky, and it did not seem long until we had left the white waters of the sponge grounds behind us, and were out over the ocean, heading by compass for the far off islands.

Out of sight of land we ran into a bad storm, which like the Red Sea, divided as we approached, leaving a narrow passage between the rain areas, through which we flew. It soon became apparent, however, that there was more trouble ahead. A curtain of inky darkness hung over the horizon, and as we approached, we saw that there was a violent storm raging under the mile-high thunderheads.

To go over was impossible, and to attempt to fly through was out of the question. We should have been beaten down and immediately swamped in the violent seas. Yet we knew that Bimini was not more than five miles away, in the center that inferno. Our gas was limited, and so, after making an unsuccessful effort to find a gap, we turned back for Andros, only to be confronted with another problem.

For some 80 miles we had not seen land, and it was accordingly necessary to resort to dead reckoning as we hurried eastward. Very soon we ran into a rain storm which stung our faces and hands as we vainly searched for the thin grey line which should appear. The moment was approaching when our gas would give out. Could we make land?

Suddenly a grey mass broke through the haze and we saw land dead on our course. Soon we could see fishing boats lying at anchor in Red Bay, the fishing settlement we had been making for. Only two miles separated us from them when, with a sputter and a cough, the engine stopped.

We were only a few feet above the sea and Captain Holland made a wonderful landing across wind. The moment we were down, he seized the wooden hatch cover, and with a few blows of a hammer, turned it into a sea anchor which he tied to a rope trailing from our bows, and which served to keep our head to the wind and control our drift.

Fortunately, the wind had dropped, but sounding showed deep water, so there was nothing to do but sit tight. We photographed each other and looked around for the possibility of escape. It was then that I found there was neither food nor water on the ship.

For an hour and a half we drifted gently north-east towards a group of cays which lay on the horizon, but it soon became apparent that the current had altered and that we were turning out to sea. Tying a rope to himself, Holland jumped overboard and found to his surprise that the water only came up to his neck. I was not long in following him. Together we started off, towing the useless plane behind us, towards the nearest of the islands.

Darkness came on with the usual rapidity of tropical nightfall, and we were left to make our way by starlight in a sea swarming with barracuda and shark, either of which might very easily have incapacitated us. More and more, slowly, we dragged the boat. Would the island never come nearer? The water was now only up to our knees.

A sudden flash of phosphorescent fire approached at an unbelievable speed, and a fish came straight at me, passing with a leap from the water right between my outstretched legs. The fish was a small barracuda. I do not know whether Holland or myself was first onto the plane.

I only remember that I lay panting for fully five minutes before either of us could get down into the sea again to continue our labor. All around strange shapes passed through the water leaving trails of liquid fire, and it was with a feeling of great relief that at 8:30 p.m., after towing for two and a half hours, and covering some eight miles, we stumbled ashore on a sandy beach at the north end of the southernmost Man-o’-War Cay.

We had no matches, but by taking off the magneto booster and the priming can of gasoline we had a very efficient method of making fire. In order to quench our thirst, we ran the radiator water off into a gasoline can and attempted to drink it. A more nauseating draught cannot be imagined. Oil and rust were mingled with a flavor of brass solder, and the mixture was lukewarm.

How we managed to retain the few drops we drank I do not know, but. retiring early to our sandy couch under the stars and keeping as still as possible, we hoped for the best.

In a few minutes we were surrounded by swarms of large mosquitoes, which did not leave us alone for a single moment all night. It is not surprising that, at the first signs of dawn, we were up exploring our island. We lighted a fire to attract the attention of any boat that might pass.

We found that we were on a small circular sand bank, covered with scrub and a few struggling palmettos. The milk-white waters lapped mournfully at the mangrove roots. There was only one bright spot in the outlook. The water was probably shallow all the way to the mainland, 20 miles away, and should we be able to make a raft we could start poling our way to civilization.

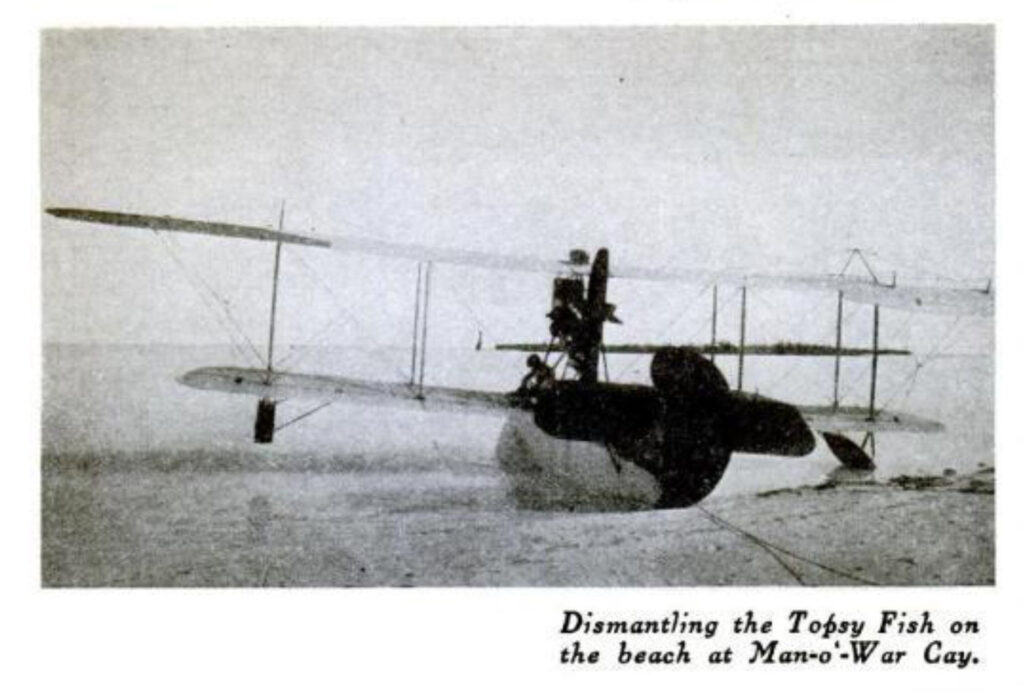

Owing to the absence of a lumber yard on our island, this scheme was abandoned. Suddenly Holland had an idea. We would dismantle the plane, put our water and clothes with the binoculars and camera in the cockpit, and tow the hull behind us. Holland had no sooner thought of this plan than he sprang into action and commenced the tremendous task of taking to pieces, a full sized flying boat with nothing but his emergency tool kit. Too exhausted to be of much use, I lay on the beach while he undid the nuts and bolts securing the engine mounting and wings.

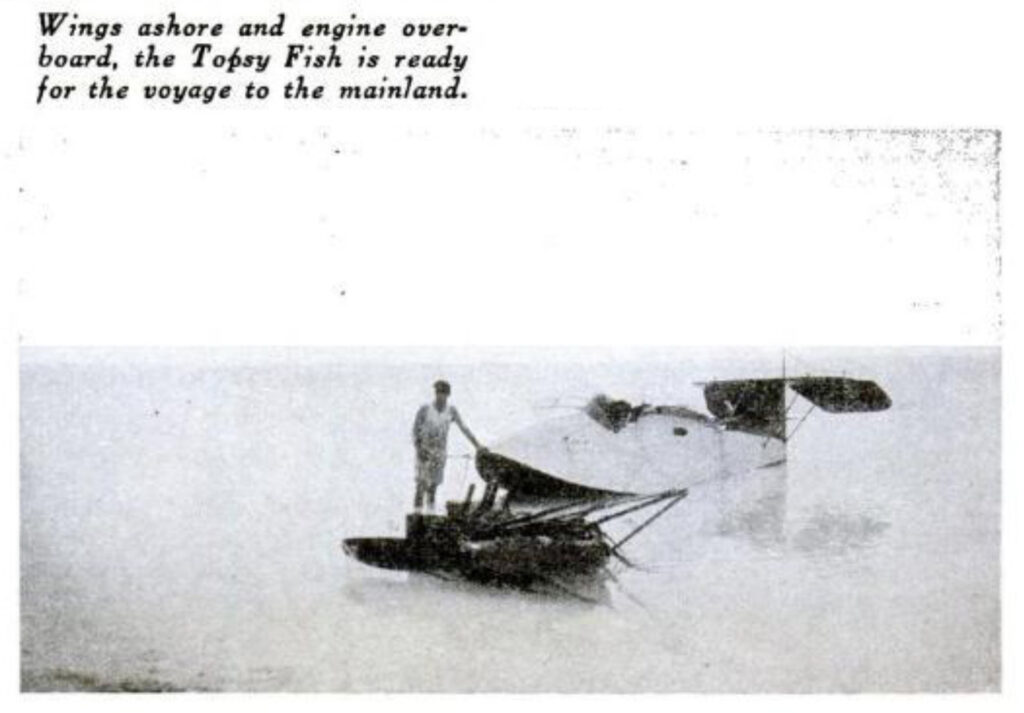

Then with great caution, we worked the wings off and dragged them above high water. During this process, I was bowled over by a wing section and half buried in a mixture of sand, clay, and salt water. From this time on, despite the burning sun, I worked in nature’s garb, an action which I afterwards regretted. After we had removed the wings, we made a rope fast to the engine on the now top-heavy hull, and rocked it until it fell overboard into the sea, missing the delicate hull by the fraction of an inch.

By noon we were ready to go, and after a rest we wrote a message in oil on one of the wings, stating that we were making for Andros. This done, we set out for the next cay, towing our hull after us. After some two miles of wading we came to a deep channel where we were forced to swim, holding onto the hull as we did so. Just as we were becoming exhausted, we again touched bottom, and we proceeded to slog on through the slimy clay which coats the coral sand eighteen inches deep. Finally, at about 4:30 p.m., we hit the beach, and after exploring the island, found that it was even more barren and desolate than the one we had left, although there were many more crabs.

A tarpaulin was stretched over the cockpit in an attempt to catch rain water, but all storms passed us on one side or the other. We saw a fishing boat, and again brought the magneto booster and can of gasoline into play, but to no avail.

At this point we succumbed to the effects of our vile beverage. We were both sick, and after feeling very bad indeed we decided to confine our efforts with the radiator water in the future to merely wetting our lips, swallowing nothing. About 7 p.m. we fell asleep, and except for the mosquitoes and the smudge fire, which needed occasional tending, we spent a peaceful night.

Up before dawn the next morning, we decided to make one great attempt to reach the mainland before noon. So, without stopping except for an occasional immersion to cool our thirst as much as possible, we struggled on through the forenoon. Mile after mile we made our way, treading on fish and crabs, and poling across deep water channels with a piece of plank, until, around the next cay, we saw a sloop only some three miles away sailing towards civilization. On we went, trying from time to time to attract the attention of the boat, but without success. Finally we watched it sail away out of sight.

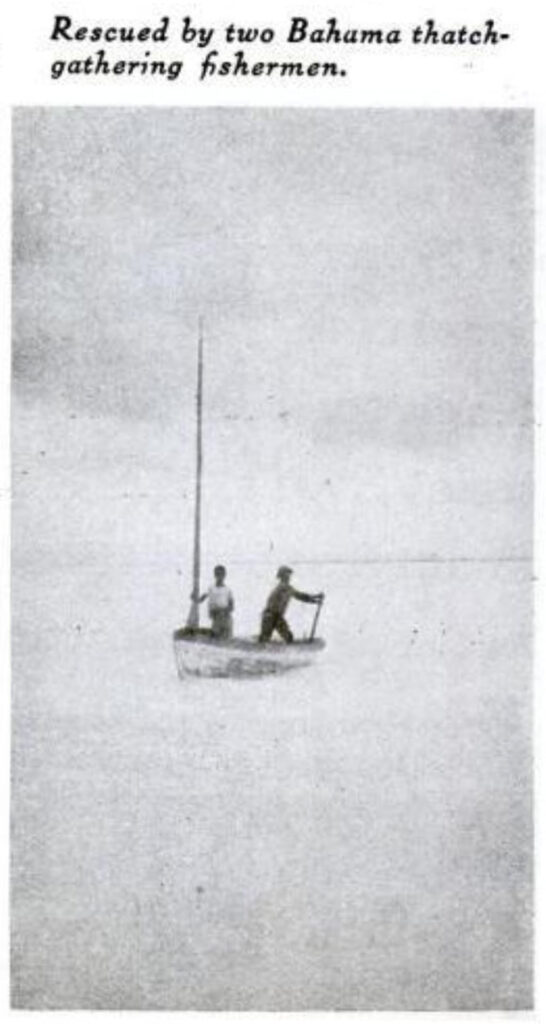

We had covered some 14 miles like this when, poling along in deep water, Holland suddenly shouted that a skiff was approaching. In a few minutes, two Lowe Sound fishermen were alongside, and we had transferred our allegiance to their sail boat, after anchoring the hull with the tool box on board.

We found that the distant land was yet another cay and that, had we landed and walked across, we should have had the bitter disappointment of seeing a deep channel stretching between us and the mainland, which lay another two or three miles beyond.

Our rescuers had no food or water aboard, as they were merely out picking thatch for their house. They at once gave chase to the vanished sloop, which was known to carry a certain amount of water, and after some two hours’ rowing and sailing, we were able to attract the attention of the captain. He dropped anchor and before long we were on board. We each drained two large mugs of water from a barrel which was kept on deck, and had some sour bread, baked after the native fashion, but very agreeable to us on this occasion.

The fishermen, who were all colored, were towing another sloop which had been damaged in the recent hurricane. We left directions with them for salvaging the hull of the Topsy Fish, and in still another skiff set off on a stormy voyage to Nicoll’s Town.

The wind had freshened, and for the next four hours our little sloop tacked backwards and forwards, taking big green combers abroad frequently. We spent a strenuous time bailing the water from the bottom of the boat. About 4:30 p.m., 48 hours after we had come down at sea, we saw a Waco seaplane making towards us over a promontory called Morgan’s Bluff. It circled around, and much to our disappointment, headed off to the west. Soon it was back again, however, and as it passed overhead the pilot, Captain A.B. Chalk of the Chalk Flying School of Miami, signaled to us that he would wait for us at Nicoll’s Town.

We arrived at Nicoll’s Town at six o’clock and were welcomed by the entire population under the leadership of Mr. O’Brien, the Commissioner. After eating some fruit that Chalk had given us, we went up to the Residency where we took a bath and changed into clean clothes supplied by the Commissioner. Here we had supper.

Seated on the piazza after the meal, we were surprised to see three men approaching us. We found that they were messengers Collie, Holt, and Russell of Nassau, who had come out in the yacht “Dorothy” with food and medical supplies. The meeting was hilarious, and we began to realize that great anxiety had been felt for our welfare in Nassau.

After a long night’s rest, I made an early morning start with Captain Chalk in his seaplane and by breakfast time we were in Nassau, and seated in my studio recounting our experiences to our friends. The “Dorothy” had gone back to collect the pieces of the “Topsy Fish”.

A rumor had spread that I had arrived in a weak and ailing condition, but I was able to show that, on the contrary, I was physically the better for our adventure. At the same time I should not want to do it all over again.

A week later, the pieces of the plane were brought into Nassau, and the work of rebuilding the ship and cleaning out the engine was commenced. The Topsy Fish will fly again, and I hope that I shall fly in her. There was nothing the matter with the plane or the engine or the pilot. We simply had sheer bad luck in regard to weather.

The ordeal experienced by Gordon Bazely and Captain Holland serves as a testament to human resilience and ingenuity. After their forced landing, the duo endured harsh weather, limited resources, and encounters with marine life, all while fighting the sea currents to reach safety. Their perseverance, along with the help of local fishermen and a rescue team, eventually brought them back to civilization. Despite the adversity, Bazely concludes with optimism, hopeful for the future flights of the Topsy Fish. This story remains an inspiring example of how courage and determination can lead to survival and triumph, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

Your interest in the stories I share means a lot to me. I’m grateful for your support and can’t wait to bring you more exciting content in the future. Thank you, and I’ll see you in the next one!

Discover more from Buffalo Air-Park

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.