Flying Through Controversy: The Tale of Gustave Whitehead

When you think of the first powered flight, the Wright brothers likely come to mind. Their famous moment at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in December 1903 is one of the most iconic achievements in history. But what if I told you there’s a rival claim—a story that predates the Wright brothers by over two years? That story belongs to Gustave Whitehead, a name less familiar but no less intriguing. His tale is one of innovation, perseverance, and, yes, controversy.

Whitehead’s life began far from the skies, in Leutershausen, Bavaria, on January 1, 1874. Born Gustav Albin Weisskopf, he displayed an early fascination with mechanics and flight. By the time he emigrated to the United States in the 1890s, he was already dreaming of taking to the skies. Settling in Bridgeport, Connecticut, Whitehead began building flying machines that were unlike anything the world had seen before. His most famous creation, the No. 21, was a marvel of ingenuity.

Now, let’s talk about the claim that has captivated aviation enthusiasts for over a century. On a moonlit night in August 1901, in a field near Fairfield, Connecticut, Whitehead allegedly made aviation history. The story goes that he rolled his No. 21 aircraft onto a makeshift runway, powered up its lightweight engine, and took off. The plane reportedly flew half a mile at an altitude of 50 feet before making a controlled landing. Witnesses described how Whitehead steered by shifting his weight, a technique that seems almost mythical today but was cutting-edge at the time.

Imagine standing in that field, watching a man defy gravity for the first time. It must have been breathtaking. But here’s the twist—there’s no photograph or detailed documentation from that night to definitively prove it happened. What we have are witness accounts, reports in local newspapers like the Bridgeport Herald, and, of course, Whitehead’s own assertions.

Whitehead didn’t stop there. In January 1902, he claimed an even more ambitious flight. This time, he supposedly flew seven miles over Long Island Sound in an improved aircraft, the No. 22. Seven miles! That’s not just a hop—it’s a journey. If true, these flights would make Whitehead, not the Wright brothers, the first person to achieve controlled, powered flight. It’s a bold claim, and one that continues to spark debates among historians.

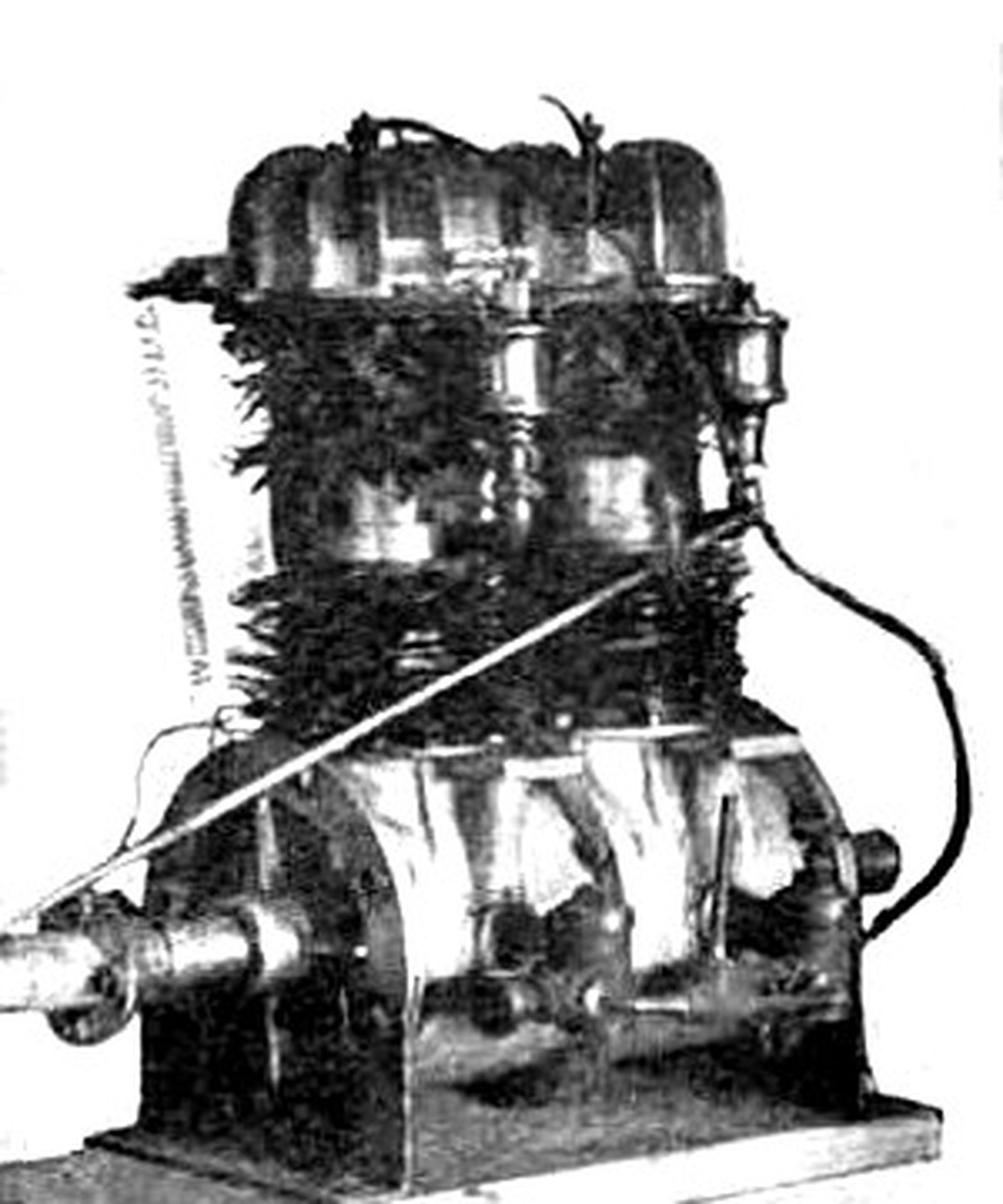

So, what’s the case for Gustave Whitehead? For starters, his innovations were remarkable. The No. 21 featured a lightweight engine, silk and bamboo wings, and counter-rotating propellers. These weren’t random experiments; they were the product of a deep understanding of aerodynamics and mechanics. Even today, modern replicas of the No. 21, built with engines similar to Whitehead’s designs, have successfully flown. It’s compelling evidence that his aircraft was capable of powered flight.

Then there are the eyewitnesses. Journalist Stella Randolph spent years collecting testimonies from people who claimed to have seen Whitehead’s flights. Junius Harworth, for instance, described watching the No. 21 soar above the treetops before landing safely. These accounts, while fascinating, were collected decades after the events. Still, they paint a vivid picture of what Whitehead might have achieved.

And let’s not forget the infamous photograph. In 1906, at an Aero Club of America exhibition, a picture was taken that some argue shows Whitehead’s No. 21 in flight. While the image is grainy and its authenticity is disputed, it has become a symbol of the mystery surrounding Whitehead’s story. In 2013, Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft, a respected aviation publication, endorsed Whitehead as the first to fly, citing this photograph and other evidence. The editorial caused an uproar, reigniting the debate and bringing Whitehead’s name back into the spotlight.

But every story has two sides. Skeptics argue that the evidence supporting Whitehead’s flights is shaky at best. Unlike the Wright brothers, who meticulously documented their experiments with photographs, blueprints, and eyewitness corroboration, Whitehead left behind very little. There are no engineering notes, no detailed flight logs—just scattered reports and personal accounts.

Even the eyewitness testimonies have been questioned. Some witnesses, like James Dickie, later retracted their statements. Others, collected decades after the events, might have been influenced by faulty memories or the allure of a good story. And while modern replicas of Whitehead’s aircraft have flown, skeptics point out that these replicas benefit from advanced materials and precise engineering, factors that might have compensated for flaws in Whitehead’s original design.

Then there’s the Smithsonian Institution’s role in the controversy. For decades, the Smithsonian had an agreement with the Wright brothers’ estate, requiring it to recognize their Flyer as the first powered aircraft. This agreement has been criticized for discouraging a fair reassessment of Whitehead’s achievements. It raises questions about how history is recorded and whose voices get amplified.

Regardless of whether Whitehead achieved powered flight, there’s no denying his brilliance as an inventor. He was a man ahead of his time, experimenting with technologies that would later become standard in aviation. His lightweight engines and innovative use of materials like bamboo and silk were groundbreaking. Later in life, Whitehead even ventured into designing vertical flight machines, making him one of the earliest pioneers of helicopter technology.

Sadly, Whitehead’s genius wasn’t enough to shield him from the harsh realities of life. Financial struggles and a lack of institutional support forced him to abandon his aviation work by 1911. He spent his later years building engines, a far cry from his ambitious dreams of conquering the skies. Whitehead passed away in 1927, largely unrecognized for his contributions.

But history has a way of rediscovering its lost pioneers. Thanks to researchers like Stella Randolph and the efforts of modern aviation enthusiasts, Whitehead’s story has been brought back into the light. In Connecticut, where his most famous flights allegedly took place, August 14th is now celebrated as “Gustave Whitehead Day.” It’s a small but significant acknowledgment of a man whose work pushed the boundaries of possibility.

So, why does any of this matter? The debate over Gustave Whitehead is about more than who flew first. It’s a story about innovation, perseverance, and the biases that shape how history is written. Whitehead’s tale reminds us that groundbreaking achievements often go unnoticed or unrecognized in their time, overshadowed by those with better resources or documentation.

For me, Whitehead embodies the spirit of exploration that defined the early days of flight. He was a man willing to take risks, to dream big, and to pursue those dreams despite immense challenges. Whether or not he truly achieved powered flight before the Wright brothers, his contributions to aviation deserve to be celebrated.

As we wrap up, I leave you with this question: Who do you think deserves the title of the first powered flight? Was it Gustave Whitehead, the forgotten pioneer, or the Wright brothers, whose meticulous documentation secured their place in history? Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Discover more from Buffalo Air-Park

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.