Tony’s Short Stories: Navy Hell Diving

Are you ready for another thrilling short story? Well, do I have something for you? This story, despite being just a single page, is a rollercoaster of excitement that kept me on the edge of my seat the entire time. I’m sure you’ll feel the same rush after reading it. Here’s a quick summary to get you started. Get ready to be thrilled!

“Navy Hell Diving” by John L. Coontz is a gripping account that will fill you with admiration for the intense and dangerous tests performed by the United States Navy. The story centers around “hell-diving,” a term that embodies the bravery of test pilots like William Crosswell who execute vertical power dives from 15,000 feet, pushing planes to their terminal velocity to test their structural integrity and the pilot’s endurance.

The narrative vividly describes the plane’s plummet and the perilous pullout maneuver, which subjects both the aircraft and pilot to extreme forces. These tests are not just thrilling; they are crucial for verifying the planes’ ability to withstand combat, including dive-bombing, a relatively new tactic. The gravity of these tests cannot be overstated.

The story also highlights the rigorous testing protocols, including speed and climb tests, gunnery trials, and various maneuvers to evaluate the planes’ performance and durability. These trials are not just tests but a crucial part of a broader effort to develop high-speed aircraft and enhance the Navy’s aviation capabilities. They reflect the advancements and challenges in military aviation during the early 1930s, a pivotal period in the history of military aviation when technological advancements and strategic innovations were rapidly transforming the field.

1932

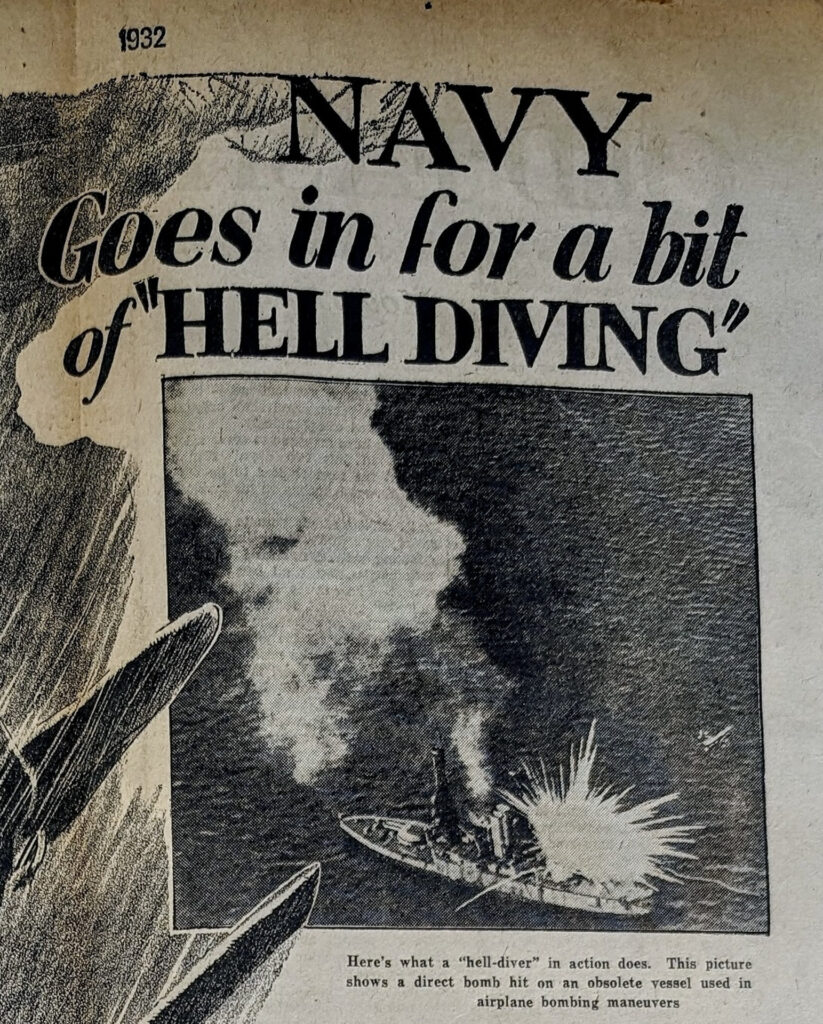

Navy Goes in for a bit of “Hell Diving”

Head straight for mother earth from three miles up, shoot downward through space at sickening speed and then pull the old boat up sharp just in time to avoid a crash.

That’s the way Uncle Sam’s boys test out new fighting planes!

By John L. Coontz

Fifteen thousand feet above the Anacostia Naval Air Station a tiny plane hangs for a second in the limpid blue. Then suddenly, as if toppled from its sky pinnacle by some unseen hand, it shoots earthward at sickening speed. American naval officials gasp. For 10,000 feet the plane roars downward like some hissing demon from hell, fighting and gasping for life.

At 5000 feet the pilot pulls back the “stick” and shoots the plane upward. For a moment it threatens to collapse. The wings groan in agony and the rushing winds sing a dirge through the taut ailerons. But the sturdy little craft weathers the challenge. It withstands the enormous pressure of air on its wings and the terrific strain on all its parts nobly. In a few minutes it rests beautifully upon the earth after a long, graceful flight which has something of a song of victory in it.

Such is “hell-diving” for the United States Navy as practiced by William Crosswell, test pilot, demonstrating a new type of combat plane for that branch of the Nation’s fighting service.

Vertical power diving is now a part of the United States Navy’s requirements of its fighting planes. It is specified as a test in all aircraft contracts following new methods of air attack developed by the navy-dive bombing. These tests call for the terminal velocity of a plane-as fast as it will go in a vertical, straight downward dive and come out. Hence the apt description, “hell-diving,” for anything may happen during one of these dives. The wings may fly off, the engine may disintegrate, the pilot may lose consciousness and crash.

“These dives range in length from 5000 to 10,000 feet or more,” says Crosswell. “It generally takes about 3000 or 4000 feet to reach the terminal velocity of a plane. Preliminary to executing one of these dives, a climb to 15,000 feet is made.

“The method of going into a vertical dive may be one of several, namely: a half-roll to an inverted position and then nosing down to the vertical or a loop and, instead of pulling out of this maneuver, allowing the plane to remain in a vertical attitude; or simply to nose the plane vertically from a horizontal position.

“The pullout from a vertical dive is probably the most severe test on a plane. Here the centrifugal force of the plane changing direction from the vertical to the horizontal or angle of ascent causes it, in effect, to weigh many times its normal weight. This tremendous weight increase plus the pull of gravity must be sustained by the wings.

“The pullout is effected merely by pulling back on the ‘stick.’ The degree of the pullout is largely regulated by the ability of the pilot to withstand the forces of nature to which he is subjected.

“The pilot is likewise subjected to centrifugal force which, if great enough in proportion (five or six times his own weight), causes his blood to rush to his head with resulting loss of vision and, if continued, loss of consciousness. This is generally termed ‘going black’ by pilots. The pilot recovers his vision and consciousness after the plane assumes flight along a straight line, which it usually does if he will ease off his pressure on the ‘stick. Complete loss of consciousness accompanies only a very few trials.

“In some of these dives the wings have left the plane. This is serious, but with luck is not necessarily fatal, because the terrific relative speed of the wind generally carries the wings cleanly away from the plane so that the pilot has a reasonable amount of protection from the fuselage. It is not a case of the wings coming back and flapping around the cockpit. If the pilot is fortunate enough not to be struck and rendered unconscious by some flying fragment, he can usually extricate himself and be none the worse for the experience excepting shattered nerves, which can be restored by a stimulant or a rest.

“The speed of the engine in these dives sometimes doubles the engine speed of the ordinary level flight. It can generally be read from the airspeed meter in the cockpit. These instruments sometimes read as high as 350 miles per hour. For this reason aircraft engines must be capable of withstanding much greater punishment than is given by their normal power output.

“Sometimes engines fail in these dives, but the present excellence of aircraft engine design makes this occurrence very rare. If the engine failure is not so serious as to cause it to disintegrate completely-which will usually wreck the plane-about the worst the pilot has to suffer is a dead-stick landing-that is, come down with the motor dead.

“Now a word about ‘terminal velocity’. It should be self-explanatory, but in the event that it not I might say that it is the maximum speed that it is possible to attain in any attitude of flight. Of course, the airspeed meter reading becomes constant when ‘terminal velocity’ is reached.”

It must not be thought, however, that the “hell-diving” test is the only severe test required by the navy of planes offered it for sale by manufacturers. In addition to being able to do a vertical dive satisfactorily, planes, if they are of the fighting and training type, must be nimble at acrobatics, be able to turn somersaults and cut other unseemly capers in the sky, such as the barrel roll and leapfrog.

All types of planes must meet certain rate-of-climb specifications, undergo fuel consumption tests, speed tests at surface and at various altitudes and surface ceiling tests. In addition to these, all combat planes must undergo gunnery-gear tests. In other words, airplanes are built for the navy in accordance with the terms of a contract which specifically guarantees certain weights, performance and suitability.

When a plane is first received by the navy at its Washington flying field it is generally given a single flight by the contractor’s pilot. This is called the “contractor’s demonstration,” the purpose of which is to show the probability of the airplane being able to meet its guarantees and to prove that it is a reasonable flying machine.

If the plane passes its “demonstration” satisfactorily, it is turned over to the flight test section of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics for trials.

A routine test begins with the weighing of the plane, empty and then fully loaded. This is done to determine the position of the center of gravity. The plane is then “fingerprinted” or photographed, the photographing covering not only the airplane with all its equipment in place, but also any items of unusual interest or peculiar construction which might be of future value.

The machine is now ready for muscular tests in the air that shall demonstrate its worthiness as a fighting craft, training ship or bombing ship, and so forth. Climb, speed, stability and maneuverability now sit at the controls.

The information obtained from the speed trials is, first, the maximum speed; second, the minimum and landing speeds; third, data for the calibration of the airspeed meter for use in subsequent tests.

These speed tests are carried out over an accurately measured course over water, adjacent to the shoreline and at a very low altitude, so that no climbing and diving errors may be introduced. Time over the course and instrument readings are recorded by the pilot on a board strapped to his leg, on which is mounted a stopwatch timed to the tenth of a second.

For the climb tests two barographs are installed for the recording of the pressure altitude, a statoscope to establish level flight condition, a thermometer to indicate free air temperatures and, in planes with a high ceiling, oxygen equipment for the pilot. So equipped, the plane is taken into the air and flown around at low altitude until the engine is properly regulated and warmed up. The machine is then brought low to the ground, the desired initial climbing speed is attained, the throttle is pushed wide open and the stopwatch started. From then on the pilot flies at an absolutely steady speed, varied slightly with change of altitude, and records the readings of his various instruments at fixed time intervals. This is continued until the indicated rate of climb is approximately that of service maximum speed that ceiling, 100 feet per minute, at which point the climb is stopped.

The pilot now turns the nose of his plane earthward, stopping at various altitudes along the way, as it were, to determine the maximum indicated speeds at these altitudes. The statoscope, which indicates the very smallest change of altitude, insures that the plane is neither climbing nor gliding when these latter observations are made.

The climb into the upper air, required of all small, high-powered fighting planes, is the classic of all tests. For it the pilot is bundled up like an Arctic explorer, wearing a heavy fur suit and boots, a full face mask and heavy gloves of leather and fur. An important part of his equipment is an oxygen tank. This is turned on at about 18,000 feet up and the outlet, in the form of a pipe stem, is held between the teeth.

From 18,000 feet up the pilot truthfully has his hands full. He must accomplish the following tasks continuously: watch his oxygen flow so that at all times he will have sufficient air to sustain himself; operate the mixture control of the engine in order that maximum efficiency may be obtained as he climbs; fly at exactly the prescribed speed for the indicated altitude; constantly observe all instruments and, every two minutes, without a moment’s variation, record the indications of no fewer than seven instruments. And all the time the air outside the cockpit registers a temperature of about 40 degrees below zero!

In the gunnery tests the guns must be fired while the ship is in the air. There must be tests also of the bombing installation, and the radio installation must be tried in flight, and all miscellaneous equipment and appliances actually operated to establish the suitability for service use.

When a plane has gone through all its tests it is a fully qualified fighter or service plane of the type designed. Tests today are much more severe than formerly, due to the fact that much more is required of them now. During the war many planes failed materially. The object now is to build planes that will stand up under all conditions without being torn to pieces.

Dive-bombing is a new form of attack, the vogue of which dates only about five years back. The Bureau of Naval Aeronautics, of which Rear Admiral William A. Moffett is chief, may be credited with a large measure of the development of this type of combat attack. In the dive-bombing operation the bomb is aimed at the target by heading the plane directly at it.

The navy only recently completed its five-year program of plane building. It had until June 30, 1932, to put the planes under the five-year program in service. As a matter of fact, the last one was in service before June 30, 1931. Congress gave the navy $85,000,000 for this program. The Bureau of Aeronautics finished it with $22,000,000 left in its till.

The recent Congress gave the bureau $220,000 for high-speed plane development. With that money the bureau has just purchased seventy-five single- seat fighting planes more than any now in use. Of this appropriation Admiral Moffett says:

“The recent appropriation by Congress of money for high-speed development will make it possible for the Bureau of Aeronautics actively to carry on a development which has been impossible heretofore, when funds were employed entirely for the provision of aircraft for active flying units. It is now possible to go into the actual procurement of a high-powered engine, and, dependent on the results obtained experimentally, to determine in what degree modern naval aircraft with extremely high-powered engines might be useful in the naval aviation program.”

Was I wrong? It’s a great story. Did you catch the pilots’ use of the phrase ‘going black’ referring to the moment when the centrifugal force of ‘hell-diving’ causes them to lose consciousness due to the blood rushing from their head? And for any flights over 18,000 feet, the pilot is bundled up like an Arctic explorer holding a pipe steam between his teeth for oxygen. That’s some crazy stuff going on there!

Thank you for joining me on another short story for Tony’s scrapbook. I can’t wait to share the next thrilling adventure with you!

Discover more from Buffalo Air-Park

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.